Written in about an hour with minimal editing, based on a prompt from George Rohac ("ennui") and Matt Zoller Seitz ("a bowler hat full of spaghetti").

*

For six months there, Jimmy Scarsdale was the most famous man in America, and the #1 box office draw in movie houses around the world. It was said that Chaplin’s The Kid was a direct response to Jimmy’s success. Most argue that it was Charlie’s competitiveness that drove him to create one of his most beloved films, but those close to the performer heard tell of the truth: he despised the cheap nature of Jimmy’s signature gag and wanted to return some kind of meaning back to the cinema. Years later, when an elderly Jimmy Scarsdale had a chance to look back on his one-time career, he would insist that, if nothing else, the movie-going public had him to thank for that.

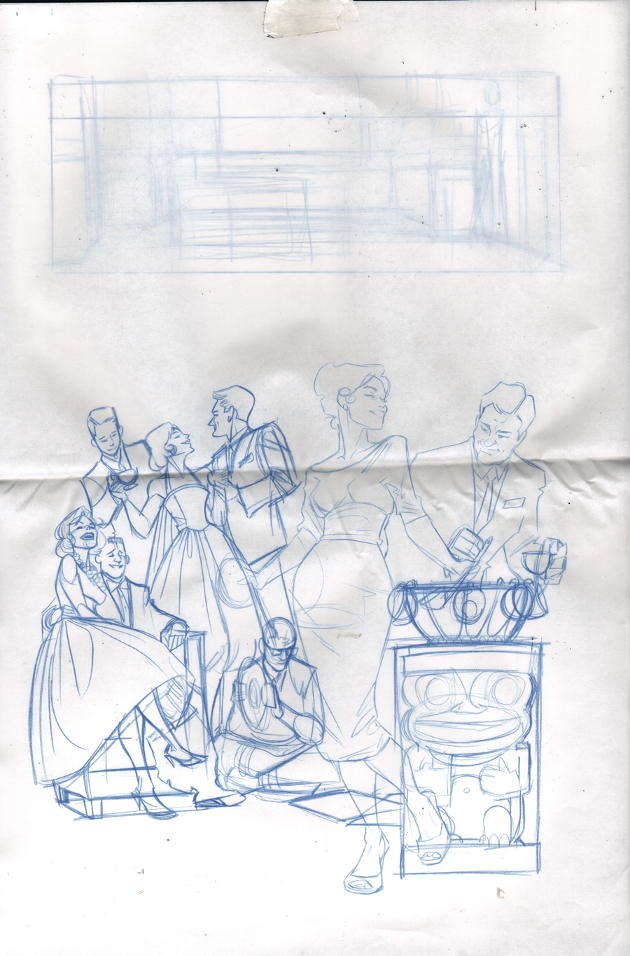

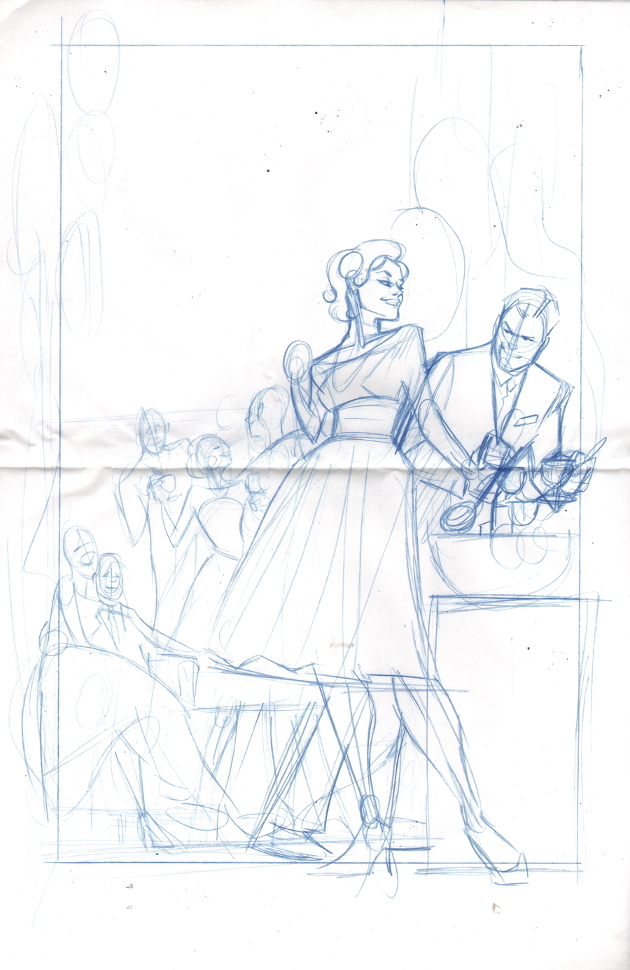

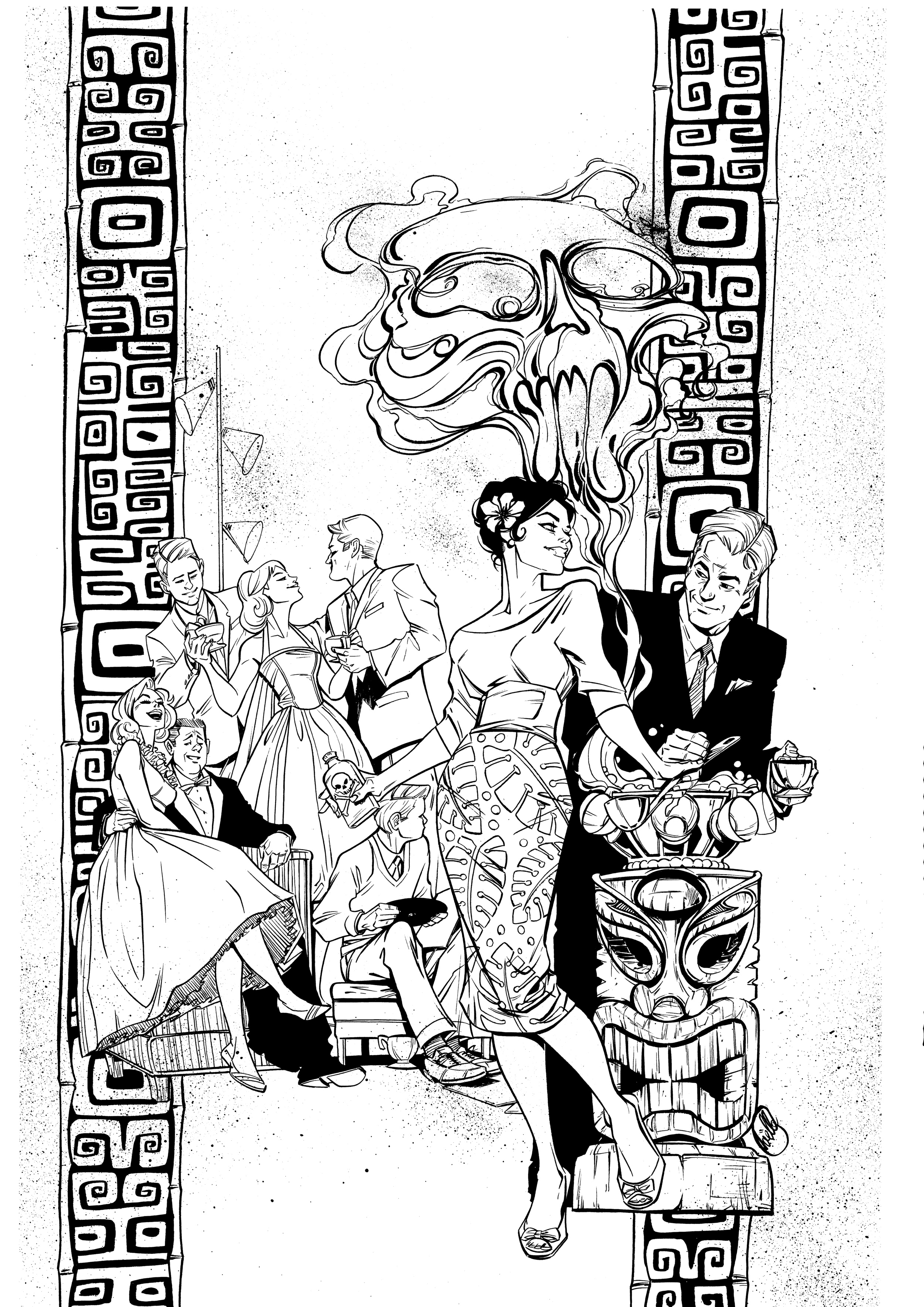

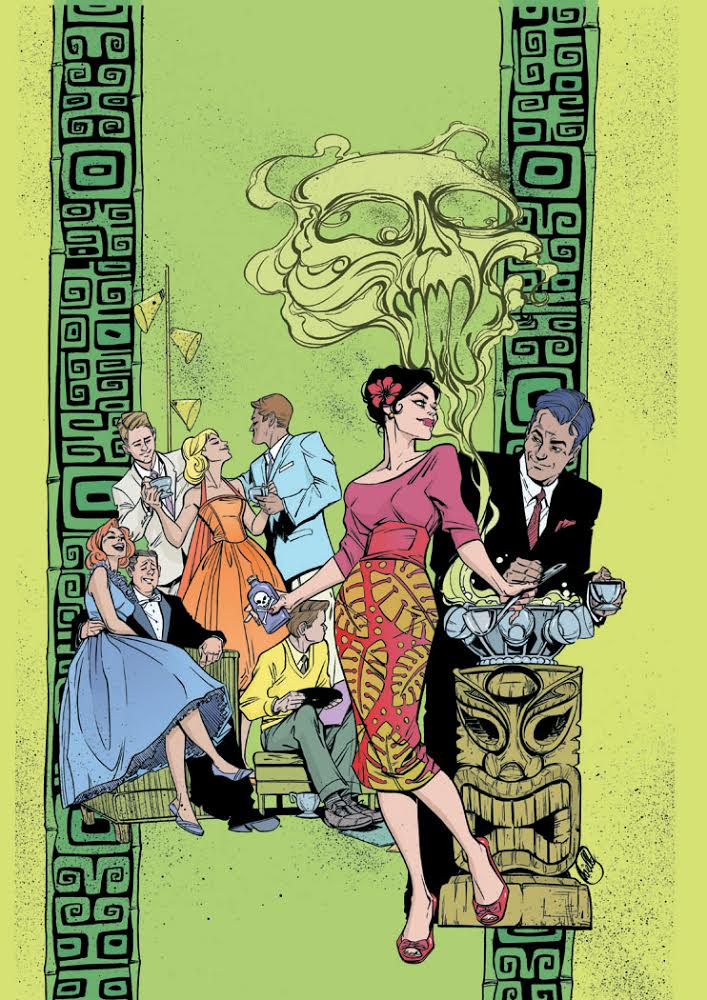

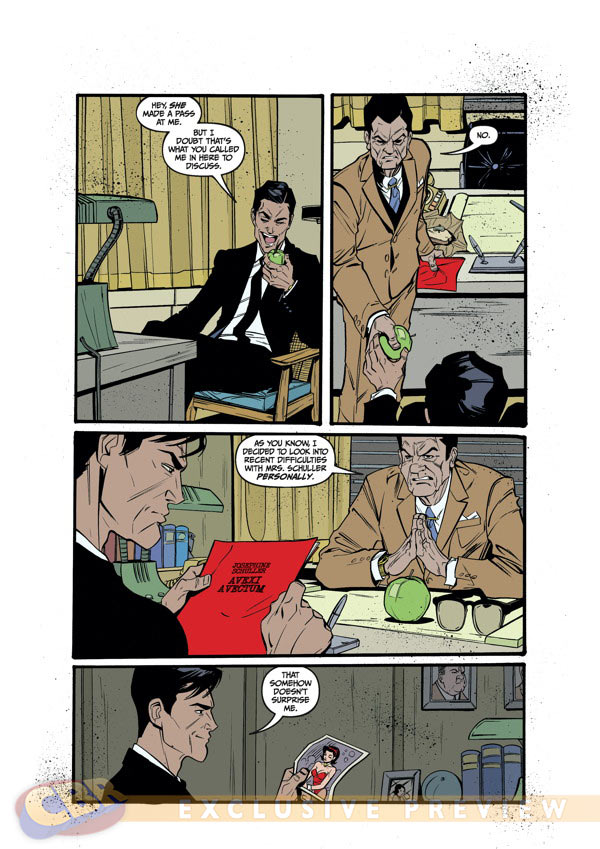

Truth was, The Kid wasn’t even done being edited before Jimmy himself grew bored with the routine that had made him famous. On a back lot in a desert in California, he sat in a rickety chair, decked out in a custom tuxedo, and holding a bowler hat full of spaghetti in his lap. They were making a New Year’s picture. The set was a lavish nightclub, the numerals 1921 hanging above the soundstage, each digit six feet tall, the light bulbs that outlined the metal currently switched off. The cast and crew were milling about, the demarcation between the two easy to spot. The “talent,” as it were, dressed to the nines, ready to celebrate the changing of the calendar; the people who put it all together were outfitted in clothes more suitable to the labor of an October morning.

Most notable amongst this crowd were the twelve dancing girls wearing rhinestone bathing suits and not much else. Their sheer stockings so thin they may as well been wearing nothing over their legs. Some of the girls draped towels over their shoulders between takes to keep warm, creating an inadvertent sensation every time the assistant director ordered them to take their marks. Every male on set would stop to watch the girls whip the towels away and expose their cleavage. There were catcalls and wolf whistles and knowing elbows exchanged, and even as early as two months ago Jimmy would have been standing with the fellas and whooping it up alongside them. Now he was the most powerful man in the vicinity and he couldn’t be bothered.

The dancing had taken a full day to choreograph and now it would take another half day to shoot, and all for what? So the latest Jimmy Scarsdale short could end up exactly the same way.

Just looking at the spaghetti in the hat made Jimmy queasy. In the years that would come, he would elaborate on these feelings, exaggerate the moment to make it sound more dramatic. “It came to a point where I’d see a plate of any pasta and I would lose my balance,” he told one gullible biographer. “The noodles would turn to worms, the meatballs to maggots, the marinara was blood. I was going to die under a mountain of spaghetti, I just knew it.”

The truth was, Jimmy felt nothing when he saw the spaghetti now. To even say it just made him bored or tired would be too much. It certainly didn’t make him hungry. Just emptiness.

There was a thrill to it once. Jimmy had gotten a real charge out of the second and third times he had done the act. That was when they really knew that he had something, that the bowler-full-of-spaghetti gag was going to make them all rich and put the struggling Poverty Row studio that had Jimmy under contract on the map. There was also the brief road tour to promote that third film, the one where Jimmy played a dandy who had happened upon a lumberjack camp and had to do some fast thinking to get in the good graces of the roughnecks. Before the screening, Jimmy would go out on stage and do the act live. At first the theater owners balked at the idea of having to clean up all that spaghetti, but once they saw how many tickets Jimmy sold, they were ready to dump whatever food he told them on their own heads.

And the crowds! They loved seeing the man from the movie screen there in the flesh. In return, Jimmy loved hearing them cheer him on. Maybe that was when things took a turn, when the studio pulled the plug on Jimmy performing live, fearing it would lessen the impact of Jimmy’s movies. “Why would they settle for the pre-recorded version when they can smell the gravy for real?”

Spaghetti Outpost was fairly indicative of the formula that would develop around Scarsdale’s persona. There was never any explanation as to why Jimmy would be wherever he was, he would just end up in some strange new locale, interact with folks there, and then about fifteen minutes in, put a bowler hat full of spaghetti on his head. Cue the laughs and applause.

Today’s production wouldn’t be any different. Auld Linguini Syne may have been more extravagant, with its musical performances and dance numbers, as well as a montage of 11 different spaghetti dumpings, one for each month of the year, as a happy Jimmy Scarsdale relived a triumphant 1920. All of this was just build-up to get them to midnight, and Jimmy ringing in the new year by having a sexy blonde ingénue in a skimpy outfit, a cross between Cupid and Baby New Year, do the ceremonial hat turn. That was the punchline.

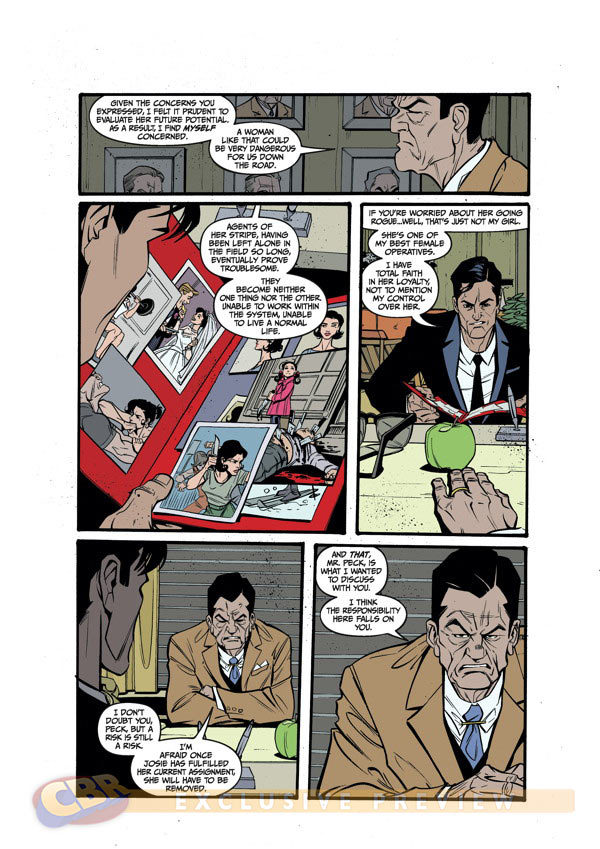

The girl was a newcomer. Deborah Stewart was 17 and eager, and Jimmy had handpicked her the way he had done all of his female co-stars since Spaghetti Outpost, the last film to feature his original leading lady, Gloria Stephens. She’d had enough of Jimmy’s roving hands, and the diva formerly known as Gloriana di Stefano had told him, “I only sleep with men who don’t smell like my grandmother’s kitchen.”

Track Jimmy’s filmography from then on, and the actresses got younger and more eager and less likely to be seen in anything else again, at least not at Jimmy’s studio, where the star might have to see one of his previous casting-couch conquests.

Perhaps that was why the excitement had faded. Jimmy could have whatever he wanted, he didn’t have to try anymore, he just had to show up and make sure his bowler hat was the right size. Seeing Deborah on set wrapped in rags to cover extremities, he remembered why he had chosen her out of the line-up of girls presented to him, but the urge to do anything about it had left him. Again, he would fictionalize this encounter later. Deborah would go on to have a healthy career right up until the sound era, and he would take credit for giving her the break that made it all possible. “It was her cupid wings,” he’d say. “She was so young and...well, with the wings, so angelic, I knew she was special and had to be treated as such. Like a kid sister, not a potential ex-wife.”

That myth would be much better than the one where a comedian in the midst of washing-out couldn’t get it up.

Perhaps the later version was partially inspired by what a nice girl Deborah Stewart really was. She approached Jimmy timidly, a modest hand on her breast bone, the other hovering lower, the actress slightly embarrassed by the costume that would make her a star and give her a gig for many December 31st celebrations to come (“Ring out the old with Hollywood’s sexiest New Year Baby!”).

“Mr. Scarsdale, sir?” she said.

Jimmy only grunted in response.

“Mr. Scarsdale, I just wanted to thank you for this opportunity. It means a lot, and I don’t know that I can ever repay you enough.”

This would have normally been his cue to make some suggestions for how she could really thank him, but instead, Jimmy took a deep breath, caught a snootful of fumes from the red sauce, lightly burped, and said, “Not a problem, kid. Just try not to splash any on ya’ when the big moment comes.”

“Can I ask you something, sir? Is it true what they say, that you based the whole thing on a prank from your schooldays?”

Deborah, like everyone else, had heard the publicity version of the origin story, and outside of a handful of people who had been on the set for Springtime Serenade, the light romantic picture that had been the debut of the hat joke, no one had any reason to doubt it. Jimmy had never been asked to vouch for his own press bio before.

“No, kid, that’s not true. You want to know what really happened?”

“Oh, yes! Please!”

“What really happened was I was supposed to have third billing on Serenade, playing the sidekick to Eddie Graham, the comedic relief while he romanced Gloria Stephens. That shrew took a disliking to me from the get-go, and had I known she was sleeping with the director, I may not have made a pass at her in the first place. Thanks to her I kept getting my scenes cut and pushed out of frame, to the point that I got so mad that I went to the lunch table and filled my hat full of noodles.”

“And you wrote yourself a new scene?”

“So to speak. My initial plan was to walk up to Gloria and pour the spaghetti on her head. If you watch the film again, you’ll see it. I walk up to her, am about to tip the bowler in her direction, only to realize at the last second that, if I did, I’d never work again. That’s how I ended up putting the hat on my own head, and the rest is, well...”

Before he could finish that thought, Jimmy and Deborah were called to set. They were ready for the big scene where Jimmy would come out of his reverie, the countdown reaching 1 and then, as the last calendar page flipped and the giant 1921 came to life, Deborah’s Baby New Year doused Jimmy in spaghetti. It was the first time someone other than the comedian himself would do it. Jimmy thought this was just as well. He didn’t really have the energy to do it himself.

This big moment should have been the highlight of Jimmy Scarsdale’s career, but instead, it was the beginning of the end. Auld Linguini Syne was the first of his movies to make less than the previous film, and by the end of 1921, the Tramp was King and no one wanted to see a man covered in pasta. Jimmy’s bowler had been replaced by Chaplin’s. Critics would later argue that audience’s disliked the self-congratulatory tone of the montage. In his private thoughts, Jimmy chalked it up to the fact that he just didn’t care anymore. “In comedy, you have to be committed, or the joke falls flat.”

Like many old stars, Jimmy would find some renewal in television. Early variety shows would bring him out either to dump the spaghetti on himself, or to have their host or some guest star do the dumping for him. His last appearance on the boob tube was in the late 1960s, a cameo on Laugh-In, where in a throwback to Auld Linguini Syne, Goldie Hawn would dress up like Deborah Stewart and wish everyone a happy New Year. Jimmy was in his 80s then, and nearly lost his footing when the spaghetti hit. Seeing this, Hawn grabbed him and in a sweet ad lib, kissed him on the cheek. Rather than making an old man happy, the touch of her lips and her girlish giggle put Jimmy right back in October 1920, and made him ask, “What had it all been for?”

Two days later, Jimmy Scarsdale was dead.